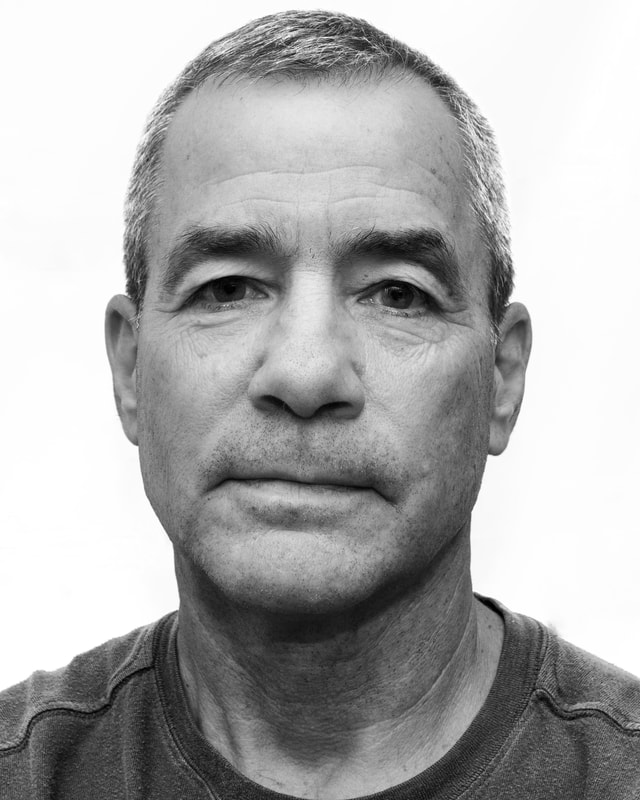

Sgt. Major Peter Arsenault

U.S. Army – 18Z

US Special Operations Command

Berlin, Panama, 1st Gulf War

1977-1999

U.S. Army – 18Z

US Special Operations Command

Berlin, Panama, 1st Gulf War

1977-1999

Peter was born in Willimantic, CT and raised in Windsor, CT. His father worked for Hamilton Standard as a military liaison and was an accomplished draftsman and educator. Peter was athletic and played soccer and hockey. “I got in trouble a lot. Nothing terrible. The cops knew who I was.” Peter told his dad he had no intention of going to college much to his dad’s chagrin. Toward the end of his senior year Peter decided he’d like to do a Post Graduate year at the Suffield Academy Prep School. The hockey coach was interested but Peter’s grades were not good enough to be admitted.

During his senior year in high school an Army recruiter knocked on Peter’s door. Peter had posters in his room of Army Rangers and Special Forces soldiers. “As a young man I always wanted to do something like that.” The recruiter told Peter he would make a good tanker. Peter said, “No way. Special Forces (SF) or nothing.” Peter passed the required tests, and he signed a commitment with the Army in April of 1977. After graduating from Windsor High School in June of 1977 Peter had two months to have fun before leaving for basic training at Fort Dix, in New Jersey.

Basic training lasted eight weeks and Peter was prepared for tough treatment at boot camp. Peter was mentally prepared and graduated without any difficulties. His next stop was 16 weeks of schooling at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas to become an Army medic, 91B Military Occupational Specialty (MOS). From there it was on to Jump School at Fort Benning in Georgia and then on to Special Forces Training at Camp McCall in North Carolina. Camp McCall was where the 82nd Airborne trained in preparation for World War II.

Phase I of SF training lasted 16 weeks and covered training in land navigation, communication, military tactics, leadership, classroom education and exercises, physical training and daily rucksack marches. Phase II focused on your Special Forces specialty and for Peter that was additional medical training.

He went back to Fort Sam Houston for 5 months of intense classroom training by doctors, nurses, anesthesiologists, pharmacists, and clinicians. Then it was back to Fort Bragg for Advanced Special Forces Medical Lab (Goat Lab) where training and classes were intense and stressful. Surgical procedures, anesthesiology, laboratory medicine, clinical care of patients, and pharmacology was the primary focus. Each Special Forces medic was assigned a goat which was always referred to as the “patient.” Students cared for and treated their assigned “patients” and kept daily health charts. A goat is used for training because their hind legs are anatomically similar to humans which is beneficial in learning how to treat combat related gunshot wounds and the complications that can arise from such an injury.

When it came time to perform surgical procedures on the patient, each medic would perform the procedure(s) overseen by veterinarians and senior Special Forces medical instructors. Additional Special Forces medics would assist as the anesthesiologist, surgical nurse, and provide medical support. Each day the class would conduct clinical or surgical grand rounds with assigned veterinarians and instructors to assess their patients. Medics would give a history of their patients, treatment conducted, discuss patient care plans and long-term prognosis. “It was a tremendous learning process.” If the patient died there was a medical review board to determine if all the proper clinical procedures had been followed or if the treatment was faulty.

The in-depth training was necessary because Special Forces teams consist of only 12 soldiers and are often inserted behind enemy lines working with indigenous personnel. If a Team member or indigenous person sustained an injury, requesting a medevac extraction isn’t always possible. The medic must be able sustain medical treatment for an extended period of time, when necessary, to keep the person alive. If you graduate, you are a Special Forces Medic.

Peter graduated from Advanced Special Forces Medical Lab and conducted 6 weeks of On-the-Job Training (OJT) at Ft. Gordon Georgia. There he was assigned to Eisenhower Army Hospital where he worked with emergency room clinicians, observed doctors during surgery, conducted sick-call and perfected laboratory skills in the hospital laboratory. Upon completion of OJT, he returned to Camp McCall for phase III.

Up to this point the officers and the enlisted soldiers trained separately. In Phase III both groups came together and formed 12 man ODA (Operational Detachment Alpha) teams. The teams would live and train together planning and conducting missions involving each team and combined teams. The capstone exercise for phase III was called “Robin Sage.” During Robin Sage Special Forces candidates are fighting in a fictitious country where the Special Forces troops train and assist indigenous forces. This simulates Foreign Internal Defense (FID) missions where they train indigenous forces and Direct Action (DA) missions where they will strike the enemy in conjunction with the indigenous forces. These are the two primary roles of the Special Forces.

Peter survived the 12 months of grueling training. After graduation Peter was a newly minted Green Beret and headed to Fort Devens Massachusetts to join 2nd Battalion 10th Special Forces Group. “Once assigned I began the intense cross-training in infantry tactics and weapons, communications, explosives, intelligence, and medicine.” When the team is inserted behind enemy lines, everyone must be versatile and proficient in each specialty. They also spent considerable time at the shooting ranges learning to handle a variety of US and foreign weapons and improving their marksmanship.

Peter wanted to go to Ranger School. “Ranger School is a leadership school using mission planning and patrolling during highly stressful situations. You are awake 20+ hours each day promoting sleep deprivation and are provided half a meal ration each day. It’s about learning about how you the soldier perform individually and operationally with minimal sleep and food. Everyone’s tired. Everyone’s hungry. It’s a very, very stressful environment. But it’s one of the best schools in the world to this day.” After completing the course in 1987, Peter returned to the 10th Special Forces Group and was later assigned to Berlin, Germany.

Peter’s role in Berlin was classified. For two years he never wore a uniform, was on relaxed grooming standards and worked in a small team and studied soviet type equipment. “The mission was completely different than typical Special Forces organizations.” Their job was to blend into the environment and conduct specialized activities that would support military operations during a war in Europe. After two years Peter felt it was time to do something different.

Peter returned to Ft. Bragg North Carolina with an assignment to Special Operations Command where he underwent a 6-month training process culminating with a deployment to the ongoing Panama invasion, also known as Operation Just Cause. In December 1989 George H. W. Bush ordered the invasion to capture Manual Noriega, the de facto ruler of Panama. He was wanted in the United States for racketeering and drug trafficking. Peter landed in the second wave as a “student” and was assigned to an operational squadron participating in combat operations. Peter was in Panama for approximately three weeks and then returned to Fort Bragg.

In 1990 Iraq adopted an aggressive posture towards Kuwait. Peter recalled the Special Operations groups began intense training for desert operations. He recalled spending a considerable amount of time away from home on Sicily Drop Zone (a training area on Fort Bragg) and the Nevada desert where they practiced long range operations and direct action drills. In August of 1990 Iraq invaded Kuwait. Training then focused on operating in Kuwait and Saudi Arabia. When Iraq refused to withdraw from Kuwait the U.S. built a collation of countries to stand against Iraq and ultimately built a significant force staged in Kuwait and Saudi Arabia. Peter deployed to Ar-Ar, Saudi Arabia, which is in western Saudi Arabia, near the Iraq border. “Our mission was to locate and identify with the potential to destroying enemy sites deployed by Iraq that could reach other Arab States and Israel.”

On a night in February 1991, his unit began a mission to identify and destroy enemy sites that were within their assigned locations. One MH-53 and two MH-47 helicopters left the Ar-Ar airfield. The helicopters were loaded with three teams and 3 all-terrain vehicles capable of desert mobility. These vehicles would be necessary to drive through the desert where there were no roads and extremely rugged terrain. The helicopters landed and their rotors created quite a disturbance. When the troops and equipment were off-loaded, the helicopters headed back to Ar-Ar. The troops remained quiet and stationary listening for anything that could indicate the presence of people or vehicle activity. Detecting no sound, the vehicles were loaded with the equipment and personnel and headed into the desert.

The first objective was to find a Remain Over Day (ROD) site. An ROD site was where the troops would hide during the day before they began traveling the next night. They traveled at night to avoid detection. Around 3 am they decided to set up a ROD before day light broke. They identified a wadi as a good site. A wadi is a dried riverbed or ravine of varying sizes. There the vehicles were positioned, and tactical nets were used to cover vehicles and equipment to create camouflage. The men settled in, priorities of work were assigned including food and sleep.

At daybreak the troops found they had settled across from a radio tower and a shack occupied by one man. The man was looking at the troops and the troops could see the facial expressions on the man. The troops immediately began to pack-up and prepare to relocate their position. They radioed the AWAC overhead to call in the position of the radio tower for an airstrike. Later that morning they heard a truck which eventually pulled in front of them. The vehicle was a water truck that provided water to nomadic Bedouins. The driver jumped out and began yelling in Arabic until he saw the camouflage netting and knew these were not fellow Iraqi’s. He ran back to his truck and sped away. There had been a quick discussion among the troops if they should kill him, but they decided to let him go. Having been compromised, the troops were forced to relocate and travel during the day which left them vulnerable to discovery. After traveling most of the day they found a deep wadi they thought would provide a good ROD.

The troops broke into teams of two and climbed up the wadi to establish observation positions. The men went into a watch and listening mode to attempt to identify any activity nearby. There were periodic reports of dust clouds which they attributed to farmers plowing their fields. They would later come to learn the dust was being kicked up by tracked vehicles looking for them. Later that afternoon six Iraqi vehicles traveling in attack formation came to a stop and Iraqi troops dismounted and began shooting. This was Peter’s first exposure to enemy fire.

The teams pulled back toward their vehicles and in the process a team member was shot once through the fleshy part of his neck and once through his ankle rendering him totally immobile. All the team was able to get back to the vehicles except this soldier. Both sides exchanged heavy fire and the Teams suppressed enemy fire despite being significantly outnumbered by Iraqi forces. Peter had a general idea where the missing soldier was and despite direct orders from his team leader, he dismounted the vehicle to find the soldier.

Peter maneuvered over 400 yards while under heavy enemy fire. “I rushed up the hill to the spot where I thought he was but when I got closer, I was dismayed to find it wasn’t him. I started calling his name and finally he answered me, so I moved to him.” After rendering limited first aid and exchanging small talk, they could see a Toyota truck with a heavy machine-gun mounted on the back headed toward their position for a possible head-on firefight. “We started stacking magazines and if the truck came around the corner, we were going to light them up.” The Iraqi truck didn’t circle back, avoiding a firefight. Back at the vehicles the commander decided to send their three vehicles to retrieve both soldiers. Peter and the wounded soldier were loaded into the vehicles. US air support arrived on station identifying and destroying 11 enemy vehicles.

The team “drove for several hours” until they reached a rendezvous site where helicopters arrived for exfil. The wounded soldier was medevac’d for treatment of his injuries. The war lasted only 100 days and Peter and his team were back in the United States by mid-March 1991.

That mission was named Buckaroo Ridge, after the injured soldier, who was from Texas. For his valor to rescue his teammate, Peter received the Silver Star.

One of Peter’s teammates had the following observation, “everyone had the chance to go get the soldier, but Pete went and did it, that’s the definition of valor.”

Peter recalled one of his teammates who considered himself an atheist though he was a great soldier and warrior. After the battle of Buckaroo Ridge, and prior to the next mission the chaplain called everyone together for a moment of prayer and reflection. From the corner of his eye Peter could see his teammate kneeling and bowing his head. “There are no atheists in a foxhole.”

After retiring from the military, he spent some time working in R&D with Special Operations and the US Army as a contractor focused on solving difficult problems for the military. He also served four years as the Chief Operating Officer helping to turnaround a business that was unprofitable. By the time he exited the business it was solidly profitable. This is something Peter is very proud of.

Peter, thank you for all your sacrifices and the missions that you can’t talk about. For you, indiscretion was the better part of valor.

During his senior year in high school an Army recruiter knocked on Peter’s door. Peter had posters in his room of Army Rangers and Special Forces soldiers. “As a young man I always wanted to do something like that.” The recruiter told Peter he would make a good tanker. Peter said, “No way. Special Forces (SF) or nothing.” Peter passed the required tests, and he signed a commitment with the Army in April of 1977. After graduating from Windsor High School in June of 1977 Peter had two months to have fun before leaving for basic training at Fort Dix, in New Jersey.

Basic training lasted eight weeks and Peter was prepared for tough treatment at boot camp. Peter was mentally prepared and graduated without any difficulties. His next stop was 16 weeks of schooling at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas to become an Army medic, 91B Military Occupational Specialty (MOS). From there it was on to Jump School at Fort Benning in Georgia and then on to Special Forces Training at Camp McCall in North Carolina. Camp McCall was where the 82nd Airborne trained in preparation for World War II.

Phase I of SF training lasted 16 weeks and covered training in land navigation, communication, military tactics, leadership, classroom education and exercises, physical training and daily rucksack marches. Phase II focused on your Special Forces specialty and for Peter that was additional medical training.

He went back to Fort Sam Houston for 5 months of intense classroom training by doctors, nurses, anesthesiologists, pharmacists, and clinicians. Then it was back to Fort Bragg for Advanced Special Forces Medical Lab (Goat Lab) where training and classes were intense and stressful. Surgical procedures, anesthesiology, laboratory medicine, clinical care of patients, and pharmacology was the primary focus. Each Special Forces medic was assigned a goat which was always referred to as the “patient.” Students cared for and treated their assigned “patients” and kept daily health charts. A goat is used for training because their hind legs are anatomically similar to humans which is beneficial in learning how to treat combat related gunshot wounds and the complications that can arise from such an injury.

When it came time to perform surgical procedures on the patient, each medic would perform the procedure(s) overseen by veterinarians and senior Special Forces medical instructors. Additional Special Forces medics would assist as the anesthesiologist, surgical nurse, and provide medical support. Each day the class would conduct clinical or surgical grand rounds with assigned veterinarians and instructors to assess their patients. Medics would give a history of their patients, treatment conducted, discuss patient care plans and long-term prognosis. “It was a tremendous learning process.” If the patient died there was a medical review board to determine if all the proper clinical procedures had been followed or if the treatment was faulty.

The in-depth training was necessary because Special Forces teams consist of only 12 soldiers and are often inserted behind enemy lines working with indigenous personnel. If a Team member or indigenous person sustained an injury, requesting a medevac extraction isn’t always possible. The medic must be able sustain medical treatment for an extended period of time, when necessary, to keep the person alive. If you graduate, you are a Special Forces Medic.

Peter graduated from Advanced Special Forces Medical Lab and conducted 6 weeks of On-the-Job Training (OJT) at Ft. Gordon Georgia. There he was assigned to Eisenhower Army Hospital where he worked with emergency room clinicians, observed doctors during surgery, conducted sick-call and perfected laboratory skills in the hospital laboratory. Upon completion of OJT, he returned to Camp McCall for phase III.

Up to this point the officers and the enlisted soldiers trained separately. In Phase III both groups came together and formed 12 man ODA (Operational Detachment Alpha) teams. The teams would live and train together planning and conducting missions involving each team and combined teams. The capstone exercise for phase III was called “Robin Sage.” During Robin Sage Special Forces candidates are fighting in a fictitious country where the Special Forces troops train and assist indigenous forces. This simulates Foreign Internal Defense (FID) missions where they train indigenous forces and Direct Action (DA) missions where they will strike the enemy in conjunction with the indigenous forces. These are the two primary roles of the Special Forces.

Peter survived the 12 months of grueling training. After graduation Peter was a newly minted Green Beret and headed to Fort Devens Massachusetts to join 2nd Battalion 10th Special Forces Group. “Once assigned I began the intense cross-training in infantry tactics and weapons, communications, explosives, intelligence, and medicine.” When the team is inserted behind enemy lines, everyone must be versatile and proficient in each specialty. They also spent considerable time at the shooting ranges learning to handle a variety of US and foreign weapons and improving their marksmanship.

Peter wanted to go to Ranger School. “Ranger School is a leadership school using mission planning and patrolling during highly stressful situations. You are awake 20+ hours each day promoting sleep deprivation and are provided half a meal ration each day. It’s about learning about how you the soldier perform individually and operationally with minimal sleep and food. Everyone’s tired. Everyone’s hungry. It’s a very, very stressful environment. But it’s one of the best schools in the world to this day.” After completing the course in 1987, Peter returned to the 10th Special Forces Group and was later assigned to Berlin, Germany.

Peter’s role in Berlin was classified. For two years he never wore a uniform, was on relaxed grooming standards and worked in a small team and studied soviet type equipment. “The mission was completely different than typical Special Forces organizations.” Their job was to blend into the environment and conduct specialized activities that would support military operations during a war in Europe. After two years Peter felt it was time to do something different.

Peter returned to Ft. Bragg North Carolina with an assignment to Special Operations Command where he underwent a 6-month training process culminating with a deployment to the ongoing Panama invasion, also known as Operation Just Cause. In December 1989 George H. W. Bush ordered the invasion to capture Manual Noriega, the de facto ruler of Panama. He was wanted in the United States for racketeering and drug trafficking. Peter landed in the second wave as a “student” and was assigned to an operational squadron participating in combat operations. Peter was in Panama for approximately three weeks and then returned to Fort Bragg.

In 1990 Iraq adopted an aggressive posture towards Kuwait. Peter recalled the Special Operations groups began intense training for desert operations. He recalled spending a considerable amount of time away from home on Sicily Drop Zone (a training area on Fort Bragg) and the Nevada desert where they practiced long range operations and direct action drills. In August of 1990 Iraq invaded Kuwait. Training then focused on operating in Kuwait and Saudi Arabia. When Iraq refused to withdraw from Kuwait the U.S. built a collation of countries to stand against Iraq and ultimately built a significant force staged in Kuwait and Saudi Arabia. Peter deployed to Ar-Ar, Saudi Arabia, which is in western Saudi Arabia, near the Iraq border. “Our mission was to locate and identify with the potential to destroying enemy sites deployed by Iraq that could reach other Arab States and Israel.”

On a night in February 1991, his unit began a mission to identify and destroy enemy sites that were within their assigned locations. One MH-53 and two MH-47 helicopters left the Ar-Ar airfield. The helicopters were loaded with three teams and 3 all-terrain vehicles capable of desert mobility. These vehicles would be necessary to drive through the desert where there were no roads and extremely rugged terrain. The helicopters landed and their rotors created quite a disturbance. When the troops and equipment were off-loaded, the helicopters headed back to Ar-Ar. The troops remained quiet and stationary listening for anything that could indicate the presence of people or vehicle activity. Detecting no sound, the vehicles were loaded with the equipment and personnel and headed into the desert.

The first objective was to find a Remain Over Day (ROD) site. An ROD site was where the troops would hide during the day before they began traveling the next night. They traveled at night to avoid detection. Around 3 am they decided to set up a ROD before day light broke. They identified a wadi as a good site. A wadi is a dried riverbed or ravine of varying sizes. There the vehicles were positioned, and tactical nets were used to cover vehicles and equipment to create camouflage. The men settled in, priorities of work were assigned including food and sleep.

At daybreak the troops found they had settled across from a radio tower and a shack occupied by one man. The man was looking at the troops and the troops could see the facial expressions on the man. The troops immediately began to pack-up and prepare to relocate their position. They radioed the AWAC overhead to call in the position of the radio tower for an airstrike. Later that morning they heard a truck which eventually pulled in front of them. The vehicle was a water truck that provided water to nomadic Bedouins. The driver jumped out and began yelling in Arabic until he saw the camouflage netting and knew these were not fellow Iraqi’s. He ran back to his truck and sped away. There had been a quick discussion among the troops if they should kill him, but they decided to let him go. Having been compromised, the troops were forced to relocate and travel during the day which left them vulnerable to discovery. After traveling most of the day they found a deep wadi they thought would provide a good ROD.

The troops broke into teams of two and climbed up the wadi to establish observation positions. The men went into a watch and listening mode to attempt to identify any activity nearby. There were periodic reports of dust clouds which they attributed to farmers plowing their fields. They would later come to learn the dust was being kicked up by tracked vehicles looking for them. Later that afternoon six Iraqi vehicles traveling in attack formation came to a stop and Iraqi troops dismounted and began shooting. This was Peter’s first exposure to enemy fire.

The teams pulled back toward their vehicles and in the process a team member was shot once through the fleshy part of his neck and once through his ankle rendering him totally immobile. All the team was able to get back to the vehicles except this soldier. Both sides exchanged heavy fire and the Teams suppressed enemy fire despite being significantly outnumbered by Iraqi forces. Peter had a general idea where the missing soldier was and despite direct orders from his team leader, he dismounted the vehicle to find the soldier.

Peter maneuvered over 400 yards while under heavy enemy fire. “I rushed up the hill to the spot where I thought he was but when I got closer, I was dismayed to find it wasn’t him. I started calling his name and finally he answered me, so I moved to him.” After rendering limited first aid and exchanging small talk, they could see a Toyota truck with a heavy machine-gun mounted on the back headed toward their position for a possible head-on firefight. “We started stacking magazines and if the truck came around the corner, we were going to light them up.” The Iraqi truck didn’t circle back, avoiding a firefight. Back at the vehicles the commander decided to send their three vehicles to retrieve both soldiers. Peter and the wounded soldier were loaded into the vehicles. US air support arrived on station identifying and destroying 11 enemy vehicles.

The team “drove for several hours” until they reached a rendezvous site where helicopters arrived for exfil. The wounded soldier was medevac’d for treatment of his injuries. The war lasted only 100 days and Peter and his team were back in the United States by mid-March 1991.

That mission was named Buckaroo Ridge, after the injured soldier, who was from Texas. For his valor to rescue his teammate, Peter received the Silver Star.

One of Peter’s teammates had the following observation, “everyone had the chance to go get the soldier, but Pete went and did it, that’s the definition of valor.”

Peter recalled one of his teammates who considered himself an atheist though he was a great soldier and warrior. After the battle of Buckaroo Ridge, and prior to the next mission the chaplain called everyone together for a moment of prayer and reflection. From the corner of his eye Peter could see his teammate kneeling and bowing his head. “There are no atheists in a foxhole.”

After retiring from the military, he spent some time working in R&D with Special Operations and the US Army as a contractor focused on solving difficult problems for the military. He also served four years as the Chief Operating Officer helping to turnaround a business that was unprofitable. By the time he exited the business it was solidly profitable. This is something Peter is very proud of.

Peter, thank you for all your sacrifices and the missions that you can’t talk about. For you, indiscretion was the better part of valor.